During my study sessions, I encountered Managing for Excellence: The Guide to Developing High Performance in Contemporary Organizations by Bradford & Cohen. It is a topic which fascinates me, and I’ve decided to share some insights these authors had already in 1997.

In Chapter 2: The Manager as Technician or Conductor: Heroic Models of Leadership, this concept of heroic leadership is thoroughly analyzed. It’s concept derives from The Lone Ranger, mysterious cowboy who shows up on the white horse to overcome great odds in solving the problem of the day. His job never stops: after all, the world is filled with evildoers and helpless townsfolk. Someone has to be responsible for seeing that no harm comes to the hardworking and innocent.

This concept of Lone Ranger is historically inaccurate depiction of Western frontier, which was filled with communities where top priority was mutual assistance: community barn raising, fire fighting and reciprocal protection. But, as we all know, myths do not have to be accurate to be powerful: myths reflect a culture’s needs at a certain point in time.

What are the assumptions of Heroic Model?

- It is the manager, not the members, who is responsible for seeing that the problem gets solved, getting the right data out, coming up with the solution, or making the decision.

- It is the manager who is responsible for seeing that the member work together in carrying out the solution.

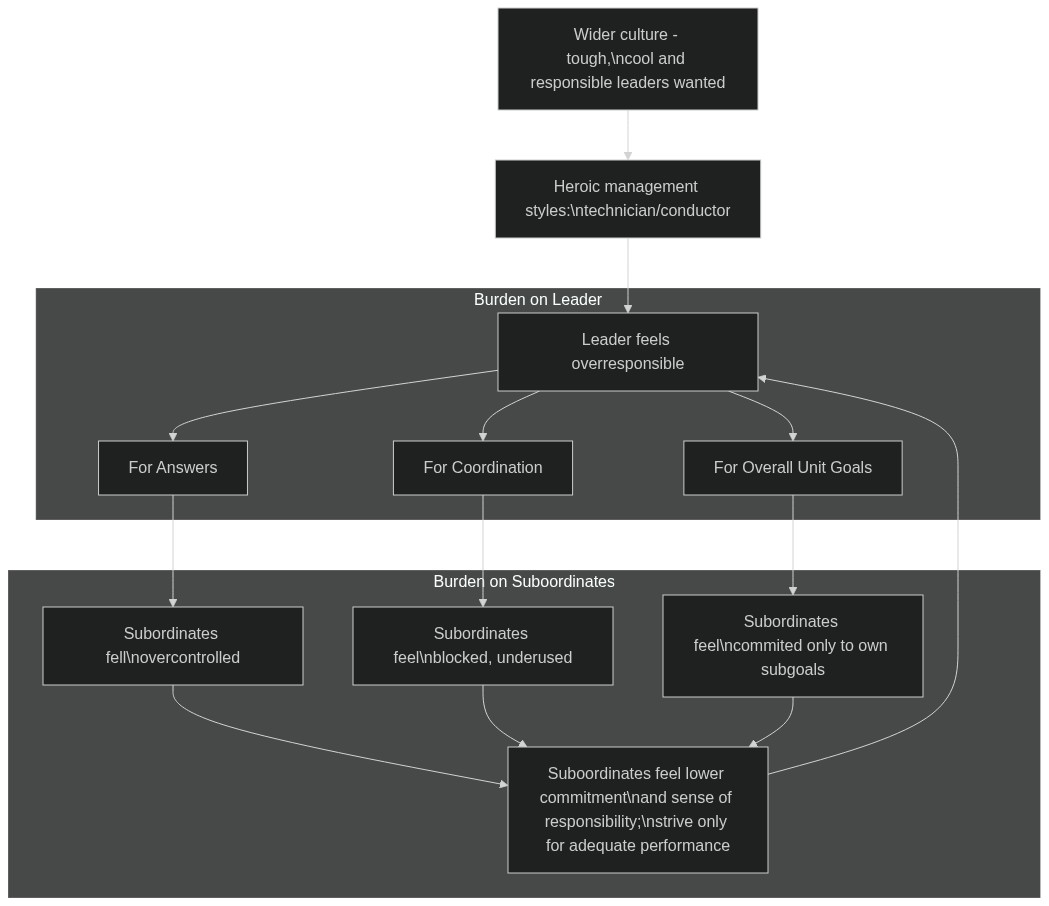

All of this leads to self defeating cycle.

Degree of control manager exerts will insure adequate performance, but it will prevent excellence from being obtained. Manager’s responsibility is increased, and at the same time, mechanism are put in place that block the upward flow of communication and the commitment of a subordinate.

Heroic Manager sees others as helpless: after all, heroes do protect the hardworking and innocent. Taking sole responsibility for the problems leads to a retreat of subordinates to their own parochial interest: when subordinates are constantly rescued, treated as weak and unable to cope, they lose motivation and become increasingly passive. This response from subordinates “proves” to the Heroic Manager that more help is necessary. And so the cycle repeats.

Authors analyze heroic management through two variants:

- Manager as a Technician

- Manager as a Conductor

1 Manager as a Technician

This is the manager with high degree of technical skills. And this has it’s benefits: knowledge is a powerful source of influence and it is less likely to create resistance than insisting on compliance due to higher rank.

This style places great demands on the technical competence of leaders. Those who are successful with it in complex task situations tend be expectational, which in turn reinforces the idea that great leaders are born, not made.

In practice, this style of leadership is exerted through having complete control of all activities, that are closely watched by manager. No change can be made without an approval, which is demoralizing to staff. All too often, this manager jumps in and does the work, which ultimately leads to a disaster since he cannot be at the top of technical knowledge: at one point in time, he will begin to deliver outdated (or sub-par) answers, which will lead to increased frustration from subordinates.

One of the worst consequences this style brings is that all of this ‘jumping in to solve problems’ will lead to bright subordinates departure, since the Technician will solve all challenging problems. Not to mention that Technician will focus exclusively on technological problems, to the detriment of human factors. Human problems require flexibility, improvisation, listening and patience. In this sense, technological problems are preferred over human problems: they don’t talk back. Technicians love technical problem solving, but hate the messiness of people problems.

Final effect:

- Limit of organizational effectiveness.

- Limit of subordinate development.

2 Manager as a Conductor

Manager as a Conductor has his eyes opened: Technician style does not work. Task will be accomplished not by managing task, but by managing people. Conductors accept the notion that management is getting work done through others, but they believe they must work very hard to stay in charge and on top of others to prevent chaos and inertia.

Which leads to the following conclusion: this style spotlights the leader as the central, heroic figure who orchestrates all the individual parts of the organization into one harmonious whole.

In addition to using interpersonal style with subordinates, Conductors tend to use impersonal form of control: administrative systems for staffing and work flow as a tool to control subordinates’ behavior (management by objectives, management information systems …). Usage of systems as these help achieve planning and coordination, and it leads to reductions of hands-on management.

To show real-world usage of such an example, authors present a dialogue between Conductor and subordinate, wherein subordinate describes the problem, and Conductor is preparing a solution by finding out how to use force, charm and political skill to coordinate action. Given Conductor’s social expertise, this could very well be an excellent solution: but how much did subordinate learn in this process? Not much. Again, the Heroic Management leads to hindrance of subordinates’ progress to excellence, and it reinforces the heroic ideal of a manager, which will lead to burnout and fall of an organization.

Summary of problems with this leadership style is as follows:

- Conductor’s concern for greater coordination of subordinates leads to minimization of subordinate concern about the overall integration of the various parts of the unit. When subordinates know that all communication and important decision flow through the manager, they can most freely pursue the narrow interests of their own subunits. They don’t have to worry about balancing diverse specialized concerns to achieve overall departmental interest: that is the leader’s problem.

- Due to interdependence of subordinates’ tasks, disagreement will inevitably arise. When these disputes cannot be easily and mutually resolved, the natural tendency of subordinates who are coordinated by Conductor is to go to boss: meaning, him. Not only is Conductor put into the awkward position of having to come up with the all-wise solution; each subordinate is encouraged to push only his or her viewpoint, which can lead to subordinates withholding or distorting of information and reluctance to accept compromise or a creative solution that satisfied both parties.

And this is the crux of the issues: Conductor suppresses subordinate development. They are not led to increase their abilities and skill, they are not forced to take wider perspectives. This, in turn, hinders their advancement in the organization.

On issue of control: Conductor is exerting so much control that subordinates feel overcontrolled, which in turn leads to subordinates investing considerable energy in regaining control of themselves, which in turn forces Conductor to work harder and harder to maintain control. And so the cycle continues. Conductor’s day-to-day job starts to resemble chess board, with plenty of possible moves and counter-moves.

Do note that Conductors use systems and procedures as a control device, rather than tools to help subordinates perform. But, again, this will lead to subordinates disengagement: no system can’t be beaten if those subject to it do not accept it’s intended use (one form of beating control is to do just the minimum necessary to get by). This, in turn, leads Conductor to build system with even more elaborate controls. And so the cycle continues.

3 Summary of problems with Technician & Conductor

- Both styles lead to adequate performance of subordinates, but not to excellence.

- Both styles overuse the task abilities of the leader, and underutilize the competencies of subordinates.

- Both styles fight with treadmill:

- Technician with greater degree of complexity of technological problems.

- Conductor with greater systems of control, which subordinates try to overcome.

- Both styles demotivate subordinates.

The following table presents when each model is appropriate:

| Feature | Technician | Conductor | Postheroic |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Subordinates work independently. | ✅ | ||

| 2. Subordinates work simple tasks. | ✅ | ||

| 3. Environment is stable. | ✅ | ✅ | |

| 4. Subordinates have low technical knowledge compared to boss. | ✅ | ✅ | |

| 5. Subordinate commitment not needed for success. | ✅ | ✅ | |

| 6. Subordinates do complex tasks. | ✅ | ✅ | |

| 7. Subordinates require considerable coordination. | ✅ | ✅ | |

| 8. Environment is changing. | ✅ | ||

| 9. Subordinates have high technical knowledge. | ✅ | ||

| 10. Subordinate commitment necessary for excellence. | ✅ |

Should managers who use Heroic Leadership refrain from supervising, since it will lead to better results? Yes.

But, ‘no-boss’ approach is hardly a long-term, viable answer to the problem of increasing subordinate commitment and responsibility for achieving excellence. Absent leader is not the answer in situation of ongoing complexity. Or, in other words, do not throw baby out with the bathwater. Someone needs to allocate work, monitor, coordinate, select employees and so on: do all the 10 roles of Manager Mintzberg set out. But, how will Postheroic Manager do this? Let’s find out in next chapter.